It isn’t uncommon to scroll through your newsfeed and see an article or post pertaining to a controversial topic like religion in schools, the separation of church and state— or Trump talking about Bible classes.

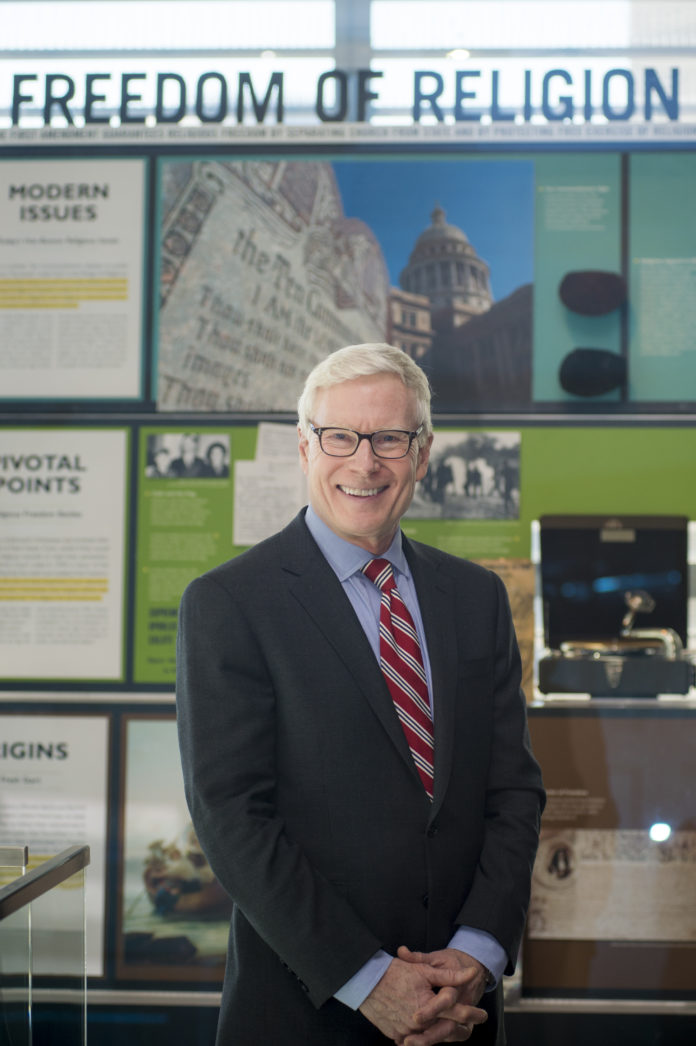

I sat down with Dr. Charles Haynes of the Freedom Forum Institute in Washington, D.C. and the founding director of the Religious Freedom Center to discuss what Bible literacy means and how the country can navigate through this sensitive topic without violating the First Amendment.

MillBuzz: What inspired you to create the Religious Freedom Center? Was there a certain experience that lead you to create that?

Haynes: Yes, my background is in religious studies; my doctorate is in religious studies. I left academia to get involved in human rights work. What I was interested in is finding a way to address freedom of conscience or religious liberty in our country and our public life, and particularly in our schools. So I’ve had a lifelong interest in, how do schools get the First Amendment right? Because for most of our history, we’ve gotten it wrong. In other words, we either impose religion through the public schools, that was much of the early public school history, and then in more recent times, many public schools have excluded religion out of fear of controversy, misunderstanding of the Supreme Court or other reasons. My vision from decades ago, from the 80s really, was to say, how can we get beyond those two failed models of religion in schools? Does it have to really be that we are going to fight forever about religion in schools? Is it the choice between no religion at all in public schools? Is one way of understanding the First Amendment the wrong way or religion is imposed, either someone’s religion or religion in general, to the public schools? Those are not the right two choices, and we’ve been stuck with that saddle for much of our history. My idea in the founding of this center— there were predecessors to this center at the Freedom Forum and museum, so this is the latest name glorified work. But the work that I’ve crafted over the years was really directed at trying to find a way to get religious liberty, to get the First Amendment right in public education and in our public square, because we do more than public education. We are talking today about public schools and that’s been a very important, big part of my work and my career. Let’s try to get it right.

MillBuzz: The term Bible literacy and religious literacy have been circulating around. Because of your large background in this area, how do you define religious literacy?

Haynes: For public education, religious literacy must be defined within the Constitution. That is to say it is learning about, or study about or teaching about religions and beliefs in public schools. Literacy is an academic enterprise. In other words, that’s the mission of schools— literacy. This is one of the important competencies that students need to be educated today in our country and in our world. So that’s what the literacy part means. The religious part is really the academic treatment of religion in the curriculum, just like the academic treatment of other subjects, like history, literature and so forth. Religion only interests the public school in the curriculum if it’s treated like an academic subject.

MillBuzz: Have you seen this definition of religious literacy change over time? Nowadays is it more of a sensitive subject?

Haynes: Well I think it’s a deeply misunderstood subject. There are many people over time and even today, including some teachers and administrators who think that religion in schools in the curriculum is forbidden by the First Amendment— that the Establishment Clause, or separation of church and state, means that you can’t talk about it or that you can’t deal with it. And we still face that myth about the First Amendment even though we’d tried mightily for decades now to educate people about the true meaning of what the Supreme Court said about religion in schools. The Supreme Court has made clear many times that they have struck down state-sponsored religious practices in schools— teachers leading prayers and so forth, or devotional Bible readings. Those are unconstitutional because they’re promoting religion through the school, through the government, which is a violation of the First Amendment. But the Supreme Court, every time it made those kinds of rulings, went on to say “Please understand we don’t mean that you can’t study about religion or that students shouldn’t study about religion.” After all, the Court would say if you want to be educated, you have to learn something about religion. You can’t learn about history or literature or much else if you don’t know something about religion, including the Bible. It’s just part of what it is to be educated. That is still tough because we talk about religion in schools and many people still here say ‘You’re going to push religion, or promote it or use government to impose it on kids?’ And that is, of course, unjust and unconstitutional.

MillBuzz: What do you think is the first step toward teaching religion constitutionally in public schools?

Haynes: Well, the first step is to understand the bright line, and the bright line is that public schools may neither inculcate or inhibit religion. They must be places where religion is treated with respect and if religion comes into curriculum, it has to come in as an academic subject. That is the bright line, it can’t come in devotionally. Now, I immediately have to add that students are not the government. So there are many ways in which students may express their religious commitment, views or even practice their faith during the school day that are not violations of the First Amendment. So students can get together and they can pray together, they can read their scriptures together or alone, they can hand out religious literature at public schools subject to reasonable time place manner restrictions. If the secondary schools allow other extracurricular clubs, they can have a religious club and meet together and worship there during the club period. There’s a long list of things where religion comes into public schools as

MillBuzz: Do you see any other challenges besides being objective when it comes to teaching religion?

Haynes: Well, there are quite a few. Teaching isn’t easy, anyway. Let’s parallel this to teaching politics. Social studies teachers who have to deal with political issues—that can be dicey, controversial and difficult. It’s not that religion is the only difficult subject, but it has its own special difficulty because we’ve been fighting about it for 150 years on how to do it in schools. Teachers are not generally prepared; they don’t have a religious studies background. Most of these teachers didn’t take religious studies when they were in college as part of their preparation for teaching. Religious studies is a field, and like other fields, it has its own special way that you have to think about it. For example, if I were teaching about Hinduism, I have to be very careful to let students know if there are any approaches within Hinduism that are different. There are many different perspectives. I don’t teach it as monolithic. There’s not just one Christianity or one Islam or one Hinduism. I also have to understand that religions change over time in how they understand themselves. I also have to understand how to help students see what people in those traditions practice, what do they do and how do they see the world? It’s not just “Here are the Four Noble Truths, or here is the Eightfold Path or the Ten Commandments.” It has to be richer than that to be appropriate teaching about religion. There are all sorts of skills and knowledge that to do this right, a teacher needs.

MillBuzz: Do you think that the most encompassing name for a religion class is something along the lines of “Religious Studies” or “World Religion?”

Haynes: There are two ways in which religious studies come into the public schools these days. One is what I call natural inclusion. Many social studies teachers, if they’re doing their job well, and if they’re following state standards, in most states, they’re going to be talking about religions, beliefs, world history, US history, government and so forth. Because that’s where it naturally would come up. You can’t really teach US history properly without talking a good thing about religion. Just look at all of our documents in our history. Until the modern period, most of our presidents have biblical references and other religious references in their letters and speeches. And it’s shaken our culture. In other words, it comes up all the time, not just in the colonial period, that religion has really been at the heart of almost every important social movement in American history. Civil Rights is a good example, child labor reform, building hospitals, caring for immigrants. All of this has to do with religious speech of different kinds. A good U.S. history teacher is going to talk quite a bit about religion. So that’s one way— natural inclusion. English literature is another example. If an English teacher doesn’t do something on biblical literacy and the King James version of the Bible particularly, you don’t really know much about English literature. Shakespeare alone has thousands of references to the Bible. So you need some biblical literacy in order to read a modern novel, to read Faulkner, to read almost anybody— you’re going to need some biblical literacy for your students. So that’s how it comes up naturally. There are other subjects, too. But the other way would be a course. Now so far, that’s an elective for the most part because it’s more challenging in a school district. They could have a required religious studies course and there is actually one school district in the U.S. that does and that’s Modesto, CA. I helped them get this started years ago. They require a religious studies semester of all ninth graders. And they teach some of the major traditions in that semester. That’s one school district in the country out of thousands that actually has a required religious studies course. Everybody else is either electives or there are some who have required courses that have a big slice of religious studies, like history course where there are a number of weeks on religions of the world. I’ve run into that. But the religious studies courses are getting more plentiful and we’ve had them for a long time, both Bible literature courses and world religion. Those are the two most common that we find around the country.

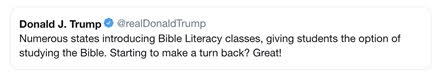

MillBuzz: How do you feel about Trump’s tweet about Bible literacy classes in schools? Do you think instituting Bible classes would be promising for students or cause a lot more harm than good?

Haynes: That’s a good question because I’ve been working on the Bible issue in schools for many years. I think this is the latest effort by some Christian groups to restore what they think has been lost of public schools. They want to restore exposure in schools to religion and particularly their religion. That comes in waves. When I first did the draft of guidelines on how to deal with the Bible in public schools, which we published in 1999 and 2000, and it’s still widely used, I got together with conservative groups— National Association of Evangelicals, Christian Society, People For The American Way, American Jewish Committee. We agreed on guidelines on what the role of the Bible is in a public school in terms of student rights and so forth, and what a Bible course elective might look like. Those guidelines are the only consecutive guidelines available that are First Amendment-framed. The Society of Biblical Literature has more in-depth guidance for teachers on how to do it. Ours is a consensus of right to

To learn more about what Bible literacy and the First Amendment have in common, be sure to visit www.FreedomForumInstitute.com to learn about what Dr. Hayne’s has spent his career studying.

What do you think about studying the Bible in public schools?